- Home

- Tools & insights

- Practical guidance for managing risk

- How can risk management help you create and protect value?

On this page

- What is value?

- What does it mean to create value?

- What does it mean to protect value?

- How does managing risk create and protect value?

- Putting a value on what you value

- In the end it comes down to your decision

- Responsibility

- Locking value into strategy and planning

Managing risk creates and protects value.

All the requirements in the Victorian Government Risk Management Framework (VGRMF) are about putting in place the frameworks and processes to do that.

What is value?

‘Value’ is an ambiguous word. We use it to talk about what can be easily quantified—such as economic value, but we also experience something as valuable in more qualitative ways—such as pleasure in being outdoors, reading a book or playing sport.

So we speak about economic value which can be priced, but also social, cultural and environmental value which can be hard to quantify, let alone price. They’re all worth something to us, as individuals, communities, or a state.

To home in on what we mean by value, we can ask

- What are we prepared to do in order to have it?

- What are we prepared to give up in order to have it?

- What do we want to keep the same when everything else changes?

These questions can help with a wide range of decisions. How much are you prepared to pay to maintain cyber security for the personal information your organisation holds? What will you give up so a project comes in on time and on budget? What must we hold on to as an economy and as a society as we transition to an economy with net-zero emissions?

In addition to this, we should recognise that we live in a world where people value different things in different ways. What ‘we’ value is not necessarily what is valued by the community being served—what a community or stakeholder values may need to be discovered. There may also be inconsistency and conflict.

How we, as a public sector, deal with this is a test of our role in contemporary life. Do we allow the evaluations of one group to dominate? Do we want to argue that everything is equally ‘valid’?

Or do we create opportunities for citizens and stakeholders to deliberate together and find common ground—or even new understandings of what’s worth doing and having.

Government organisations need to consider these questions, given their responsibility to serve all Victorians equally.

What does it mean to create value?

We work and mobilise resources to produce things that we want and think are worth having, either for ourselves or others. In other words, we create something that’s of value. One of the ways an economy grows, for example, is by creating new things that others value enough to buy.

Government organisations mostly don’t have a commercial purpose—there are exceptions—but they do still create value directly or indirectly. The following examples are designed to show how.

Does your work in a government organisation create the conditions for economic growth in Victoria? For example, does it

- remove barriers to workforce participation?

- support new businesses and industry?

- design transition paths to new economic opportunities?

- foster research partnerships between government, industry and universities?

- build new infrastructure?

We can also look at social and cultural value. Does your work in a government organisation create the conditions for cultural and social change and development in Victoria? For example, does it

- educate and train people in the knowledge and skills they need for a productive and rewarding life?

- increase understanding and appreciation of the culture we have and create together?

- produce citizens who are willing to engage with democratic processes?

- build resilience to cope with crisis or rapid change?

- remove barriers to participating in life and realising their potential?

- improve the health and wellbeing of Victorians?

And then there’s the value inherent in our natural environment; does your work

- restore waterways or coastal waters?

- establish new parks or green spaces?

- increase biodiversity?

- turn urban and suburban spaces into thriving, self-sustaining ecosystems?

Each of these makes it possible for something new to be created. The economy grows. Our cultural life includes new possibilities. Our social connections give more to those who are part of them. Our environment is renewed or expanded.

As the examples show, creating value for people involves work. It involves taking a risk to achieve objectives that will make a material difference to people.

What does it mean to protect value?

We’re all beneficiaries of past work to create value like we’ve described above. But we also benefit from unearned goods such as clean air and water, land, minerals and biodiverse ecosystems.

A large part of VMIA’s insurance portfolio is about controlling the financial risks associated with loss or harm to both the value we’ve created in the past and the ‘unearned’ value.

While insurance might be able to help us to pay costs to get up and running again, some of these losses and harms are irrecoverable. It’s part of our responsibility to make sure we protect the people, places and systems we value.

Looking across the different types of value this time, does your work

- maintain infrastructure?

- ensure we have clean water to drink?

- look after public collections of art, books or other artefacts?

- safeguard the quality of education and training?

- reduce the risk of uncontrolled bushfire?

- make sure public spaces are safe and contribute to health and wellbeing?

- improve road safety?

- create preventative health programs?

Protecting value, just like creating it, involves work. Time and money are spent to maintain things, systems and places in a state that’s desirable to us. As for creating value, we need to take a risk, otherwise we won’t achieve our objectives.

How does managing risk create and protect value?

Risk is the effect of uncertainty on our objectives.

Our objectives are—and should be—to create and protect value for Victorians, so managing risk will increase the chance that we meet our objectives. It can be that simple.

But risk management also offers several strategies to test whether an objective is worth pursuing.

For example, as part of assessing risks you analyse them in detail. Is the objective worth the size and type of risk you’d be taking to achieve it? Is it worth investing in controls? Would it be better to change this objective in some way?

In defining your risk appetite, your responsible body asks itself how far it’s willing for the organisation to go to achieve this objective. This is an implicit judgement about what something is worth to the responsible body.

In building your framework, you’re making another implicit judgement about how much effort you need to invest in formal processes and governance to manage risks and achieve your objectives. The same goes for your decisions about risk maturity.

The decision to share the management of a risk only makes sense because of a shared understanding of value: you recognise that the consequences of a potential event is significant to others. You also recognise that you depend on other actors to manage the risks emerging from a situation of uncertainty.

Finally, minimising insurable risk involves detailed analysis and decisions about balancing certain costs in the present against possible costs in the future. It involves balancing financial costs and a realistic assessment of the risk of harms and losses most of us would prefer not to happen at all.

Risk management also offers several ways to evaluate the costs and benefits of our work to achieve objectives. Many of the topics above will help you here too but we can also further demonstrate how risk management can be useful.

When deciding how to control a risk, you weigh up the cost of doing so against the benefit of achieving this objective. It also requires you to think about opportunity cost—what objectives or risk you’ll give up in order to control this particular risk.

In working out your tolerance for risk, you decide how much you’re willing to bear before calling off your pursuit of the objective. This tolerance is, in many cases, a quantitative threshold.

Your key risk indicators are essential to your evaluation of the costs and benefits. They also tell you when your risk is changing and your objectives to create and protect value are in danger.

Putting a value on what you value

Putting a value on something in quantitative terms can be difficult, particularly things, places and systems that have social and cultural value.

Sometimes an evaluation is necessary because in the end, pursuing an objective costs money and organisations, especially in government, need to show value for money.

It’s worth doing when you need to

- identify new sources of value

- demonstrate how the value your organisation creates and protects underpins other value

- compare what would otherwise be difficult to compare on equal terms

- justify large expenditures to the government or community

- consider whole-of-economy change

- make sure that social and cultural goods are given the appropriate weight in deliberation.

Parks Victoria’s Valuing Victoria’s Parks is an example of a recent effort in the Victorian Public Sector to do this analysis and evaluation. It quantified how Victoria’s parks contribute to tourism, honey production, water supply and carbon storage, as well as social cohesion and Indigenous cultural connection.

To do this kind of evaluation, economists use

- price

- observations about what people do when they have options

- what people say about what they value.

This paper, Demystifying Economic Evaluation, gives an overview of different ways to put a value on what we value.

Situations where it may be of value to do this work would be in working out the costs and benefits relating to various scenarios for economic transition to a net-zero carbon emissions economy, or the impacts of building large infrastructure.

It would be less worthwhile for projects with straightforward instrumental value, such as a decision in invest in IT services, or when what’s at stake is compliance with legislation. Projects with a smaller scope of impact will be another.

In the end it comes down to your decision

You’re making decisions that should make things better for the people, places and systems in your care. Quantifying value is only part of the answer to this question.

As we’ve said, quantifying value isn’t always worth the effort. You need to decide when it’s worth investing the resources in analysing and assessing value.

In other cases, the decision about what’s the best thing to do cannot be computed, nor should it be. For example, the Victorian Public Sector is working together on reforming our response to family violence simply because this is the right thing to do, not because of the difference to the state’s economic productivity.

Making a decision isn’t a procedure. It’s a responsibility.

In the end, we need to make decisions and be prepared to justify them in plain language to our public, the government, our communities and stakeholders. That justification will be in the language of value.

Responsibility

We’ve said that you can only perform well if you manage risk well and unpacked the various dimensions of good performance—including the ethical dimensions.

Your responsible body and executive team need to be champions of this approach to decision-making and be sincere, thoughtful users of the language of value. They need to show how it makes a material difference to the organisation’s success. It’s how they show their leadership.

The language of value should be apparent in their decisions about

- objectives

- the organisation’s risk appetite

- tolerances

- risk culture

- opportunities to share risk

- minimising insurable risk

- organisational change

- policies, strategies and plans

What about decision-makers across the organisation?

All decisions about how to reach objectives should be grounded in the decisions that the responsible body and executive team make about how to pursue objectives.

Decisions about how to create and protect value should be made with the same focus and rigor as businesses show when it comes to pursuing commercial objectives, perhaps more. After all, government organisations create the conditions in which it’s possible for businesses and individuals to pursue the objectives that matter to them.

Finally, this is the foundation of your accountability. Value is not abstract. It’s something we work for and mobilise resources for and we can show how it makes a material difference to wellbeing and the future of Victorians.

-

Tools

This guide to decision making by the Australian Institute of Company Directors with The Ethics Centre shows how value is at the heart of decision-making.

Locking value into strategy and planning

We have given examples of the work that’s done in the public sector to create value and protect it. We’ve discussed how putting a value on what you value can feed into your cost-benefit analysis and shown how it informs decision making.

But how would this play out in practical terms?

- consult with communities, stakeholders and experts about what they value and what a valuable service would look like to them

- use deliberative forums to arrive at new and richer understanding of what is valuable

- use deliberative forums to decide how public resources could be deployed

- explicitly describe, in qualitative terms, what value is being created and protected, and for whom

- carry out fundamental research to identify what’s valued and valuable, and analyse its value in quantitative terms (as Parks Victoria did)

- carry out cost-benefit analysis by using this broader analysis of value and use it to guide decisions about projects

You can then use the knowledge and information you generate to

- make sure your risk management embeds this approach to value

- set your objectives, shape your strategies and inform your planning.

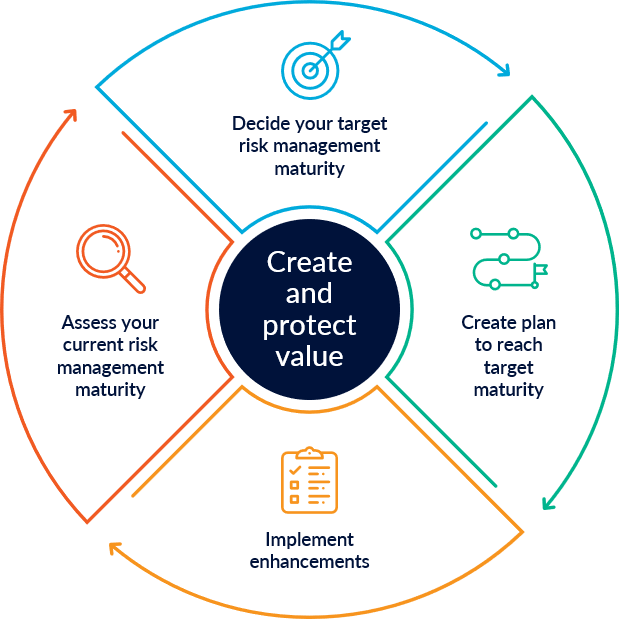

Finally, a mature organisation recognises that it needs to take a risk to create and protect value for Victorians. Make the most of the Risk Maturity Benchmark to be the organisation that can do this for the people, places and systems in your care.